Isabella Bird was born in England at a time when girls were not even entitled to a formal education, yet she went on to travel the world. She wrote prolifically about her countless adventures and became a celebrity back home. When she arrived in Japan in 1878, she ignored the warnings of other westerners and set off on an ambitious journey from Tokyo to Hokkaido. She spoke no Japanese, and her only company was her guide, Ito.

Along the way, she travelled by rickshaw, on horseback, by boat, on foot and even rode a cow or two. Although she packed a folding bed, she wasn’t afraid of roughing it. Determined to explore “regions unaffected by European contact,” she forded rivers, waded through mud, stayed in run-down yadoya (Japanese inns), and stoically put up with vicious pack horses and inflamed insect bites.

Japan had only opened its borders to the outside world ten years before Isabella sailed into Yokohama, and although western visitors had since flooded in, most didn’t venture further north than Nikko. When Isabella contacted a British government department for travel advice, they sent back an itinerary that was missing 140 miles of her intended route due to “insufficient information.”

Isabella wrote, “Comfort was left behind at Nikko!” Her journey off the beaten track took her through endless farming villages and hamlets, where she roused the curiosity of the locals: “In these little-travelled districts, as soon as one reaches the margin of a town, the first man one meets turns and flies down the street, calling out the Japanese equivalent of ‘Here’s a foreigner!’”

Modern day visitors to Japan are often impressed by the high level of hygiene, particularly when compared to other parts of Asia. However, accommodation standards in rural Japan in 1878 were somewhat lower than today, and Isabella had to deal with rats, fleas and even snakes in the various yadoya at which she stayed. “Beetles, spiders and woodlice held a carnival in my room after dark … The night was very long,” she wrote despairingly of one such place.

The “Food Question” presented Isabella with another problem. Perhaps surprisingly for a woman who plunged boldly into the unknown with little trepidation, she dismissed Japanese food as “fishy and vegetable abominations,” and seemed to subsist mostly on rice, eggs and occasionally some meat, when Ito could acquire it (meat wasn’t commonly eaten at that time). It’s hard to imagine what she’d make of the fact that Japan now has the most Michelin three-star restaurants in the world!

Her route from Nikko took Isabella first into Fukushima, where she saw the volcanic Mount Bandai “rising above the smothering greenery of the lower ranges into a heaven of delicious blue.” She then travelled to Niigata by river. Coming straight after what she described as “the very worst road I ever rode over,” this boat trip offered some welcome respite for her aching muscles.

She stayed for a week in Niigata with a British government official and his wife, reveling in the luxury of a house with solid walls and doors rather than paper screens. From there, she headed into the mountains and through some of the most isolated villages she had yet seen. Far from the relative modernity of Tokyo, the poverty in this region shocked her: “Very few horses are kept. The shops contain the barest necessities of life … These people never know anything of what we regard as comfort.”

Arriving in Yamagata, Isabella passed through the town of Akayu, famed for its hot springs. Apparently it offended her Victorian sensibilities, for she described it as “one of the noisiest places I have seen … [The] bathing sheds were full of people of both sexes, splashing loudly.” She decided not to spend the night there, instead travelling a further ten miles along the road until she found somewhere more to her liking.

Her journey through Yamagata went smoothly, thanks to a well maintained road running the length of the prefecture, and she wrote, “Yamagata-ken impresses me as being singularly prosperous, progressive, and go-ahead.” One place that didn’t impress her quite so much, however, was the former castle town of Shinjo: “There was a hot rain all night, my wretched room was dirty and stifling, and rats gnawed my boots and ran away with my cucumbers.”

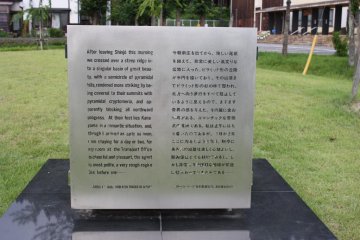

Leaving Shinjo, Isabella wrote, “We crossed over a steep ridge into a singular basin of great beauty, with a semicircle of pyramidal hills … At their feet lies Kaneyama in a romantic situation.” She decided to spend two days in the picturesque town, where Ito even managed to secure a chicken for her supper. It is likely that Isabella was the first westerner to visit Kaneyama, and today in the town there stands a monument in commemoration of this.

After some well-earned relaxation in Kaneyama, it was time for Isabella to continue on her journey north, deeper into the wilds of Japan.